As the world continues to navigate and execute the largest vaccination effort on record, immunization information sharing across the entire health and care ecosystem is paramount. Public health interoperability is a system to “support the ability of different information technology (IT) systems and applications to communicate, as well as exchange and use information, to ensure that the right information can be shared between public health agencies and healthcare providers in a timely manner to address public health crises and epidemics,” according to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Immunization is a key component of all global public health efforts, and currently prevents 2-3 million deaths every year from diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, influenza and measles. We are continuously learning about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, which has proven to be the primary path forward that will enable pre-pandemic activities to resume globally.

Opportunities for Improved Immunization Interoperability

The U.S. and its territories manage and operate 61 independent immunization information systems (IIS) located within state and city health departments and governed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Immunization Services Division (ISD). Over two decades ago, a national immunization registry was explored but was not enacted due to several political hurdles; instead, IIS were developed at the local and state level, and although they follow national standards, they are operated independently, governed by local law and policy. Consequently, the current environment may require EHR market suppliers to customize products to accommodate local law and policy of IIS across the country.

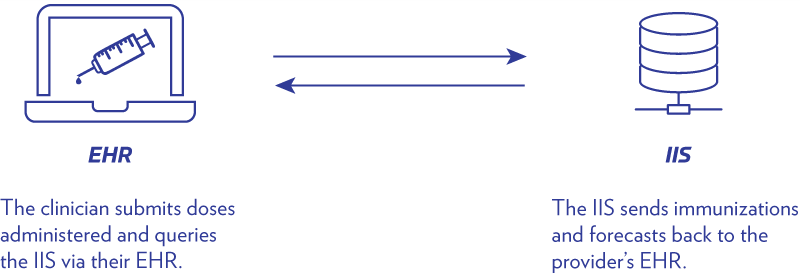

In spite of this federated public health system operated at the state level, there is a dynamic level of immunization information exchange already taking place. Currently, immunization interoperability typically involves inputting patient-level data into the EHR, the IIS receiving the information and consolidating it with existing immunization records. These longitudinal records are then available for querying at the clinical point of care, and immunization and public health programs also use the data for population-level decision-making and management. This bi-directional process is also used to help support inventory management through ordering and automated decrementing, distribution, reminder recall, outbreak response, and many other functions. Figure 1 represents one popular use case for immunization data sharing.

Figure 1: Immunization integration bi-directional data sharing

Due to the hundreds of thousands of active standards-based interfaces between clinics, hospitals, pharmacies and IIS utilized today, state and local health departments and healthcare providers who need to exchange data do not always use the same information systems, data formats or data standards. This can lead to inconsistencies and potentially inaccurate data, handicapping our public health system from properly surveying and reporting communicable diseases, as well as running the risk of clinicians under- and over-vaccinating their patients and increasing the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases in a population.

As the world continued to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and worked to refine the ongoing distribution and administration of vaccines, an extraordinary number of decisions needed to be made in rapid succession. Some of the technical and programmatic considerations included, but were not limited to:

- Defining “essential” versus “non-essential” workers

- Coordinating the distribution of vaccines from the manufacturer to health systems, retail clinics and other vaccination sites

- Identifying the order in which individuals will receive the available vaccines

- Reporting and tracking vaccinations given throughout jurisdictions

- Organizing health education campaigns on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines to reduce hesitancy

The ongoing dynamic of federal, state and local law and policy further complicates an already complex process impeding our ability to achieve true interoperability. We continue to navigate the reality of diverse clinical information systems, federated public health systems and varying data standards, formats and policies making the reality of seamless public health interoperability challenging at times.

Additional Public Health Considerations for Special Populations

U.S. territories and rural areas often have their own unique interoperability challenges resulting in the lack of a comprehensive view of the health needs of a population. For example, the Indian Health Services (IHS) serves the American Indian/Alaska Native population of the U.S., and this population primarily relies on regional IHS for their primary and urgent care needs where their IIS are managed and operated. The IHS immunization information systems have not been funded to consistently update their technical capabilities to interoperate with other systems across public and private healthcare, further widening the gap to preventative care and illness treatment for this population.

Similar to state IIS, the U.S. territories independently manage their IIS, but present unique challenges including issues around basic network connectivity, hardware and system updates required to achieve interoperability with EHRs. Rural areas of the U.S. historically have lower rates of immunization and obtaining a real-time, accurate and complete understanding of their community can be difficult due to the outdated technical infrastructure. This may impede the ability to provide critical information sharing with EHRs and other clinical settings.

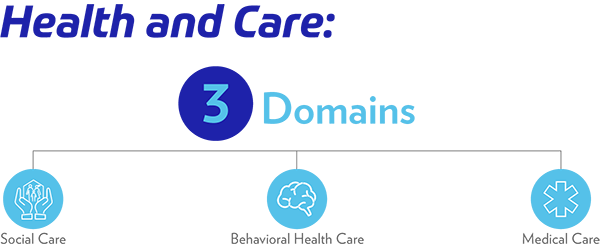

Furthermore, managing disease risk for special populations faces unique challenges, specifically for the American Indians/Alaskan Natives, U.S. territories and rural areas when preparing for and distributing a new vaccine, as they are disproportionately affected by this disease and may lack basic interoperability capabilities. American Indians/Alaskan Natives make up just over 2% of the U.S. population but are 5.3 times more likely to be hospitalized due to COVID-19 than their Caucasian counterparts, as reported in U.S. News. This is the largest disparity for all other ethnic and racial groups represented in the country. A growing body of knowledge and evidence shows that many health and care issues are exacerbated by their social determinants, or factors, – essentially where an individual is born, grows, lives, works and ages. The interplay between medical, social and behavioral care is critical to understanding the complexities around disease risk and management. Figure 2 highlights the three domains that illustrate the relationship between social and medical care.

Figure 2: Three domains of health and care

Another key consideration that rural areas are often confronted with are distribution and storage issues since many local healthcare providers and pharmacies in these settings may be small in size and cannot accommodate supplies for mass vaccination, therefore, may require a different vaccine administration strategy. U.S. territories continue to struggle with different challenges, e.g., basic network connectivity, further exacerbating the digital divide. We must continue to address these essential needs and tools to ensure they have timely access to vaccines and population-level immunization data.

Ongoing Efforts Supporting Public Health Interoperability

While complex barriers remain ahead of us on our journey to achieving immunization interoperability, meaningful work and important strides are occurring. There are many national efforts underway that recognize the multifaceted network of challenges that hinder our ability to achieve true interoperability and information sharing across the public health ecosystem, including between IIS and EHRs, and are invested in the improvement and advancement of immunization interoperability.

Figure 3 highlights several interoperability efforts anchored around improving our nation’s ability to connect the public health ecosystem, including sources of funding, purpose and key stakeholders represented. This list is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to provide a snapshot of the breadth and depth of the work occurring across the country.

|

Public Health Interoperability Initiatives |

Source of Funding |

Purpose |

Key Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) |

APHL promotes the role of state and local public health laboratories in the detection and surveillance of VPDs by improving knowledge, providing training and ensuring quality information exchange and offers AIMS, a secure, cloud-based platform that accelerates the implementation of health messaging by providing shared services to aid in the visualization, interoperability, security and hosting of electronic data. |

|

|

|

Not Applicable |

Discusses the challenges of information sharing and collaborate on ideas and solutions for a nationally consistent and sustainable approach to using electronic health data. |

|

|

|

CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) |

The Immunization Gateway (IZ Gateway) is a portfolio of components that share a common IT infrastructure. These components support the exchange of immunization data between immunization information systems (IISs), provider organizations, and consumer applications. The IZ Gateway can streamline time- and resource-intensive data exchange onboarding. It also replaces multiple one-to-one connections with centralized routing. |

|

|

|

Immunization Integration Program

|

CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) Immunization Services Division (ISD) |

Brings key stakeholders together to improve immunization interoperability, information sharing and management with the goal of assuring clinicians and IIS have timely access to complete and accurate data to improve clinical decision-making and management, increase vaccination coverage and reduce vaccine-preventable diseases. |

|

|

CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) Immunization Services Division (ISD) |

Provides IIS with information and guidance to align with the IIS Functional Standards, a set of specifications which describe the operations, data quality, and technology needed by IIS to support immunization programs, vaccination providers, and other immunization stakeholders. Published results demonstrate current status and improvements. |

|

|

|

Not Applicable |

SHIEC strives to enable the secure exchange of patient information to improve the quality, coordination, and cost-effectiveness of healthcare locally, regionally and nationally. |

|

Figure 3: Opportunities to Improve Public Health Interoperability

Investing in Public Health Infrastructure Today Enables a Healthier Tomorrow

The journey to achieving an interoperable public health immunization ecosystem may be complex, but the problem and the solution encompass similar stakeholder groups including, but not limited to, clinicians, EHRs, HIEs and IIS. Public health interoperability must be addressed collaboratively across sectors. The American Immunization Registry Association (AIRA) has outlined IIS Policies to Support Pandemic and Routine Vaccination to “ensure that policies support complete and accurate data exchange.” Successful immunization integration is imperative to public health interoperability and emphasizes the need to reinvest in public health technology infrastructure and workforce development across the health ecosystem, as outlined in CDC’S Data Modernization Initiative. Sustained, strategic investments in public health will ensure immunization information is not only available to meet today’s COVID-19 obstacles, but that our systems can seamlessly interoperate to meet our future demands as well. Health information management and technology advancements evolve at a rapid pace. Public health interoperability should be viewed with the same level of urgency to advance infrastructures that support evidence-based decision-making to improve health outcomes for patients and communities.

HIMSS Immunization Integration Program

Better health outcomes, reduced costs and higher clinician productivity

The HIMSS Immunization Integration Program is advancing the inclusion of enhanced immunization capabilities in EHRs to improve the exchange of data between EHRs and immunization information systems.